My friend sent me this poem, in German, by Bertolt Brecht, Erinnerung an die Marie A.

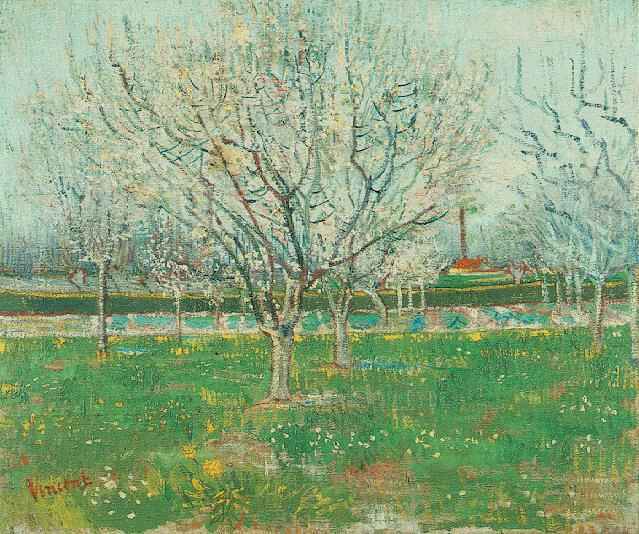

An jenem Tag im blauen Mond September

An jenem Tag im blauen Mond SeptemberStill unter einem jungen Pflaumenbaum

Da hielt ich sie, die stille bleiche Liebe

In meinem Arm wie einen holden Traum.

Und über uns im schönen Sommerhimmel

War eine Wolke, die ich lange sah

Sie war sehr weiß und ungeheur oben

Und als ich aufsah, war sie nimmer da.

Seit jenem Tag sind viele, viele Monde

Geschwommen still hinunter und vorbei.

Die Pflaumenbäume sind wohl abgehauen

Und fragst du mich, was mit der Liebe sei?

So sag ich dir: ich kann mich nicht erinnern

Und doch, gewiß, ich weiß schon, was du meinst.

Doch ihr Gesicht, das weiß ich wirklich nimmer

Ich weiß nur mehr: ich küßte es dereinst.

Und auch den Kuß, ich hätt ihn längst vergessen

Wemnn nicht die Wolke dagewesen wär

Die weiß ich noch und werd ich immer wissen

Sie war sehr weiß und kam von oben her.

Die Pflaumebäume blühn vielleicht noch immer

Und jene Frau hat jetzt vielleicht das siebte Kind

Doch jene Wolke blühte nur Minuten

Und als ich aufsah, schwand sie schon im Wind.

You might know it from that movie, Das Leben der Anderen. http://www.youtube.com/watch?

Here is an English translation if your vocabulary in German is like mine. I like to go back and forth:

http://cecilhanibal.wordpress.com/2009/07/09/bertold-brecht-erinnerung-and-die-marie-a/

Here is what Benjamin says about clouds in his essay Einbahnstrasse (One-Way Street):

Heidelberg Castle: Ruins whose debris point into the sky tend to look twice as beautiful on those clear days when the eye, through their windows or simply above them, meets the passing clouds. Through the mobile spectacle that it stages in the sky, their destruction confirms the eternity of debris.

This is H. U. Gumbrecht's translation. I'm reading his book The Powers of Philology, trying to understand what he means by a philology devoid of interpretation or hermeneutics, devoid of the search for meaning. I am wondering how he reads, as though he hopes, still, for an ideal language that could somehow be pure and forego representation, or at least the complications of the human imagination. I'm not sure I understand him. But then, he doesn't understand Benjamin:

I cannot quite follow the association that he suggests between ruins and eternity. More precisely, I do not understand why an awareness of the ongoing effects of destruction (Zerstörung) should ultimately lead to an impression of eternity (Ewigkeit) - even if this process of destruction is "doubled and emphasized by the transitory spectacle" ("bekräftigt durch das vergängliche Schauspiel") of the clouds in the sky.

He writes this at the beginning of the first chapter, called Identifying Fragments, p. 9.

What do clouds have to do with Philology? Well, along with orphaned lines, philology often deals with incomplete texts, so there is this ideal of the unified text as it was before fragmentation, before the philologist confronts the words he reads as a fragment. This ideal text, of course, is purely the invention of the philologist who can't truly grasp what this pre-fragmented text actually was. He imagines it. But what I like in Benjamin's essay is that the ruins are all there is. I don't think he sees the idealized completed castle. I think he just sees the ruins, which suggest to him the passing of time, which itself is eternal, and the clouds, passing at a quicker pace, remind him of time passing. But he isn't reconstituting the castle. He is just enjoying the contrast : eternity glimpsed through what changes eternally (the clouds) next to the slower decay of the castle, the ruins being in and of themselves complete. What I want to say is that there is no such thing as a fragment, just like there is no such thing as an orphaned line.

And that is the point of Brecht's poem for me. Things pass, but there is still this impression left, by the movement of clouds perhaps, by the turning of a wheel, the change of seasons or the sun, but not by the thing itself, which has gone, and ultimately no longer matters. But then again, the title of the poem contains a name, and an initial, so the person is remembered after all.

Or maybe all poetry is fragmentary? Perhaps all language too for that matter, and every line orphaned. But if everything is fragment and ruin, is anything?

Back from Berlin

Germany still has pock-marked buildings,

but ones you don’t see, with all the shiny,

pretty, clean, and new.

Maybe we could look at death in a new way,

or see past the loss of the past.

Maybe today, in all its glitter, is a door,

a way to move on from what came before.

Maybe there is a way to see it all through holes,

like windows, from the inside,

maybe there is a way to shed this skin,

back from Berlin.

No comments:

Post a Comment